Today my home country votes on its future. It feels strange to type that phrase “home country”, because I haven’t lived there on a permanent basis for a long time; for so long, in fact, that I am not allowed to take part in that vote, even though my future is inextricably tied up in its future. I have followed the Brexit campaign closely – the first referendum referred to by its hashtag, which is probably a sign of the apocalypse – but I deliberately avoid writing anything about it until the day of the referendum itself.

For the last few months, my friends outside the country have been asking: what will happen? I had no idea: the polls said it was increasingly an even split, but when I spoke to friends and family in the UK, I felt like an island of Remain in a sea of Leaves. I realised early on that the decision was values-based rather than evidence-based. Even I had to recognise that the best evidence the Remain campaign could muster was a case of better the devil you know, rather than something you could test against history.

Nobody knows what happens if the UK leaves, not really: I predict disaster, but I’ve been wrong before. It’s not that I don’t trust economists, exactly, it’s that nobody trusts economists after that global financial crash which none of them saw coming and all of them seem to have convienently forgotten. Economic arguments are not as solid as Remain thinks they are, but at least Remain still accept economic arguments; Leave have stopped pretending that they understand how economics works, and have just started calling economists Nazis.

That’s where my worry rests its head. There are legitimate value-based reasons to vote Leave: to rebuild a sense of identity; to renew a democratic tradition; to regain some control in a chaotic world. I think there are strong arguments against all of those, but I understand those reasons. They make sense to me. The problem is that, while those are the arguments are the port of origin for the Leave campaign, they are not the port of destination. The Leave flotilla currently moors in a harbour of desolate isolation which for some reason they believe is the gateway to the world.

The calm waters of that harbour hide serious monsters just beneath the surface. The xenophobic nature of the later Leave campaign has been well-documented, but they’re just taking advantage of what was already there. Much as I value the rich tradition of English rebellion and non-conformism and grassroots democracy – a tradition which the ruling classes have consistently written out of history – there is a sour side to it, a side that would rather retaliate against an imagined enemy rather than recognise that perhaps our generals do not have our best interests at heart.

The legacy of Brexit, I worry, is that this particular battle will continue long after the campaign itself has been lost. Half the country will be aggrieved by the referendum result, and if that half is Leave, they were already aggrieved to begin with. The leaders of Remain will forget about those people as soon as the sun sets – if they ever thought of them at all – and the leaders of Leave will be free to pursue their less acceptable agendas in the dark. The targets of their wrath will be those that they blame – not just immigrants, but also those corrupted by immigrants.

The killing of Jo Cox was shocking precisely because it an anomaly. I am barely separated from Cox in some ways: we worked for some of the same organisations on some of the same issues; we shared common friends and common views about the way the world should be. I am close to her killer Tommy Mair in a different way, a way that means that I can understand his desperation to act, the way in which his desire for the best for his country could have been polluted by drinking the waters of that harbour far too often.

There is no excuse for what he did. Despite what the more rabid portions of the old right wing believe, there is no war on. We are not enemies unless we choose to make ourselves enemies. Unfortunately some people do choose to make themselves enemies, positively relishing the role, and then they need to locate their own imaginary enemies. The Remain camp need to be aware of this – there is no equivalent group in the Leave camp, holding knife fighting classes in sweaty summer schools – and realise that this group, while useful on a tactical level, will turn on them as well as soon as they need more enemies to justify their existence.

I agree with some commentators that this referendum is about the English rather than the British, but I always relied on my British identity and I don’t know what I’ll do if it disappears like the morning mist. This is the same feeling I had when the Scottish referendum was underway: not a worry about what would happen to the UK, but what would happen to the people of the UK. The English identity never included me, because I’m not white enough. Instead I felt myself British and a Londoner, both categories that welcomed people like me, although for very different reasons. Unfortunately both of those categories are also in question now; but at least they include me.

Why do I need to be included? Because part of the problem is that elites – and I am a member of an elite – are increasingly ungrounded, living in a globalised world rather than their neighbourhood. I’m sure Jo Cox felt it, and that’s why she decided to stand as an MP in her home town. I decided to try something different: while keeping the connections to my home country, deciding to settle somewhere else and build new connections there, and to try as hard as possible to minimize the globalised lifestyle that would pull me away. It’s not been a successful experiment, but I tried.

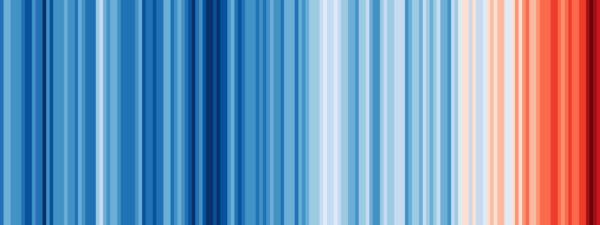

Identity is important. European was an identity that only really emerged as I was coming of age: the year I started university was the year of Maastricht; I’d spend the first half of the year working my way around western Europe, doing odd jobs and baby-sitting and car delivery and prep chef work in different cities. That identity has been systematically eroded since then, finally worn down by the way in which Greece was dealt with by the EU – specifically by the troika, and more specifically by Germany, a country which I honestly respect for its postwar trajectory.

So today I am in a quandary: I believe the European Union is important, that its achievements far outweigh the price we’ve paid for those achievements. At the same time, I believe that the European Union has failed on a moral level, and risks failing at a political level, due to the actions of its own elites. I believe that the UK should stay in the EU; that we should take ourselves out of this poisonous harbour, steer into and tack across the winds of petty nationalism blowing across Europe, out into open waters where we can set our collective course more clearly for the future.

There’s a lot more that I could write – one thing the EU has taught me is that it’s better to spill words on the page than blood in the field – but there’s no call for more words about this damned mistaken referendum. I don’t think Europe is headed back to its old wars if the UK leaves, although there might be new wars on the horizon, just not the wars the nationalist right is preparing for. I reject their wars; I reject their words; the Europe I choose was born from the Enlightenment, and I would vote Remain, if I could vote at all.