While I disagree with Longtermism, it’s a good starting point for interesting discussions about ethics. In an interview for the Future Matters Newsletter, Nick Beckstead of the FTX Foundation is asked about the intellectual journey that led him to Longtermism, and Beckstead replies:

I guess I became sympathetic to utilitarianism in college through reading Peter Singer and John Stuart Mill, and taking a History of Moral Philosophy class. I had this sense that the utilitarian version was the only one that turns out sensible answers in a systematic fashion, as if turning a crank or something.

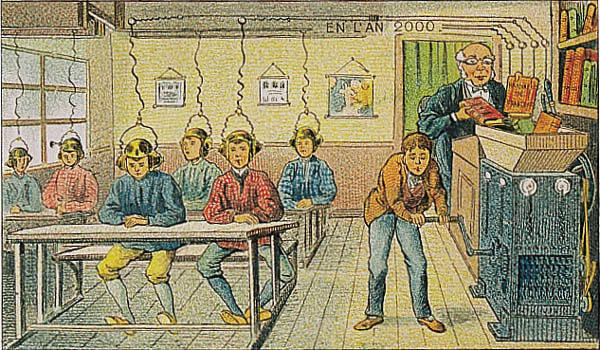

This image of utilitarianism as a crank that you turn is fascinating, because it gets to the heart of utilitarianism as the product of the industrial revolution. The idea of a clockwork universe, generated by the classical mechanics of Newton and others, made fertile ground for the spread of metaphors of mechanisation as industrialisation showed the seemingly unstoppable power of the machine. Why should ethics not work in a similar way?

An ethics that worked like a well-oiled machine – a mechanism into which one could feed the raw material of everyday life, process that material using a set and systematic calculus, and which would generate the same output every time, regardless of anything as inconvenient such as the beliefs of the machine’s operator? It’s not hard to see why such a prospect could be very appealing to a certain type of person, high on industry.

One such person would have been Jeremy Bentham, the father of modern utilitarianism, whose most widely-known idea is the Panopticon, a proposal for penal reform cast as a “simple idea in Architecture”. Yet the original idea of the Panopticon did not come from Jeremy, the philosopher, but from his brother Samuel, the mechanical engineer. In his work for Prince Potemkin in Russia, Samuel faced the problem of

management of a large polyglot and unskilled serf labour force. The difficulties of organizing them, making them answerable to discipline and supervision while reaching even minimal levels of output, were daunting. The problem quickly sparked a solution in Bentham’s mind that took a physical form. If supervision could be established in the centre of a common space, from a higher vantage point, then the task became feasible. From there, a single individual might oversee large numbers of workers.

Gillian Darley, Factory

Jeremy developed this idea and promoted it consistently. Even when translated from a factory into a prison, the panopticon was not so much a site of surveillance as it was a site of industry made possible by that surveillance. Bentham wrote a series of letters to a friend in England setting out his idea, and Letter XIII is entitled “Means of Extracting Labour”:

Understanding thus much of his situation, my contractor… will hardly think it necessary to ask me how he is to manage to persuade his boarders to set to work. Having them under this regimen, what better security he can wish for of their working, and that to their utmost, I can hardly imagine… The confinement, which is [the boarder’s] punishment, preventing his carrying the work to another market, subjects him to a monopoly; which the contractor, his master, like any other monopolist, makes, of course, as much of as he can.

Jeremy Bentham, The Panopticon Writings

I bring in the Panopticon to make clear just how much utilitarians were a product of an industrial way of thinking. They needed utilitarianism; as all of society was shifting to this way of thinking, a new ethics was required for this new age. You can’t make your case if people don’t understand your language, and so the calculating language of utilitarianism could be used to make the various cases that would occupy reformers such as Bentham.

Effective Altruism is set on a foundation of utilitarianism, and so the key arguments for longtermism are similarly founded in that industrial logic. Longtermism casts civilisation as a machine for maximising some total amount of happiness, with individual people the raw material for its workings. This is of course the same type of logic that has alienated so many people, destroyed so much of the environment, and given us so much human progress.

I tend to think, however, that Effective Altruism is not the utilitarianism of the industrial age, but utilitarianism updated for a post-industrial age, its arguments made not with the metaphor of the machine, but the force of finance. At its core Effective Altruism is simply an investment strategy, a way of calculating Return on Investment, and a source of career advice for people trying to find their way through the landscape of late capitalism.

What does this mean for utilitarianism? In many ways we’re post-industrial, and if we no longer live in an industrial age, it seems unlikely the ethics of the industrial age will be sufficient, if they were ever sufficient at all. The language of finance is doing the job of concealing that fact from us; finance claims to be about the long view, but is of course as myopic as any human endeavour, simply because humans are involved.

All philosophy is based on the disposition of the philosopher, and that disposition is shaped partly by the times in which the philosopher lives. It would be naive to expect anything else, and it would be equally naive to ignore that fact when considering the merits of their arguments. We don’t discount ancient Greek philosophers just because they have nutty ideas about nature, but we take some care to separate out the wheat from the chaff.