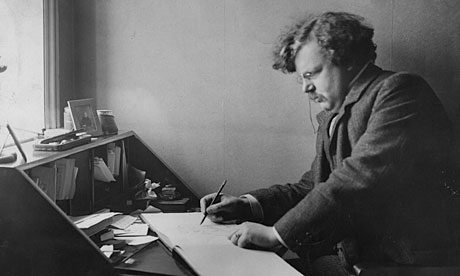

Chesterton’s fence is frequently cited – and not just by conservatives – because it has a simplicity that is difficult to disagree with. It’s an excellent description of one of the basic tenets of conservatism, which I used to find a compelling argument for taking conservatism seriously on its own terms, despite my own politics.

In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away.” To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: “If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it.”

“The Drift from Domesticity“, in “The Thing” (1929)

The principle is cited frequently but always out of context. When you look at it in context, the argument starts to look a little shaky; and then when you go back to the argument on its own terms, you see the glaring problem with it.

The problem is that, even in Chesterton’s day, none of the reformers he so clearly disdained failed to see the use of the fence; it was simply that they disagreed with people like Chesterton that that use was worth preserving the fence for.

Chesterton himself acknowledges this later in the same essay, but fails to extend any charity to his opponents beyond that:

If he knows how it arose, and what purposes it was supposed to serve, he may really be able to say that they were bad purposes, or that they have since become bad purposes, or that they are purposes which are no longer served.

But the argument that the reformers do not understand doesn’t wash any more. The fact is that those people – not all all of them, and not all the time, but enough of them, and for most of the time – understand very well what they’re protesting about in principle, if not in detail.

In fact I would assert that they likely understand it better than the people who object to the protests, at least if the recent kerfuffle over statuary is anything to go by, where the defence of statues falls to those who know nothing about them, for whom it is not a factual debate.

The tragedy of the conservative is that they live in modern times; the paradox of “conservatism” is that it was created by modern times. There was no need for that political position until the status quo began to shift in the new ways that characterised modernity.

Thus conservatism is doomed to fight the same fights again and again and again. The same criticism – these people simply don’t understand what they’re protesting! – is deployed constantly by conservatives all the way to the present day and about roughly the same issues. It may not surprise you to learn that Chesterton believed,

Among the traditions that are being thus attacked, not intelligently but most unintelligently, is the fundamental human creation called the Household or the Home.

This is at the core of the essay, but what emerges from the full text of “The Drift from Domesticity” is that Chesterton is defending a vision of domesticity that was not shared – either in theory or practice – by a large number of his fellow citizens at the time.

My complaint of the anti-domestic drift is that it is unintelligent… There are a multitude of modern manifestations, from the largest to the smallest, ranging from a divorce to a picnic party.

Chesterton’s argument might sound familiar – people of his own time didn’t see “picnic parties” as anti-domestic because of “the literature and journalism of our time” – as does the sense that this is a rearguard action; that the battle has already been lost.

Chesterton wants that battle to be decided “in a philosophical fashion”, but this is sleight of hand. He doesn’t just want to have a debate about the anti-domestic drift; he wants to decide who is allowed to have that debate based on whether they meet his philosophical criteria.

There is of course no disagreement that humans form households or that humans need homes; but the disagreement is not just over the definition of Household or Home, but who gets to set that definition. Chesterton’s fence is being erected to exclude somebody.

While the principle which Chesterton laid down is a useful one, and still worth referring to in defense of conservatism, the actual use to which Chesterton put it, however, was invidious; a weak-tea attempt to exclude his opponents rather than to defend his principles.

If a wealthy young lady wants to do what all the other wealthy young ladies are doing, she will find it great fun, simply because youth is fun and society is fun. She will enjoy being modern exactly as her Victorian grandmother enjoyed being Victorian. And quite right too; but it is the enjoyment of convention, not the enjoyment of liberty…. The girl who likes shaving her head and powdering her nose and wearing short skirts will find the world organised for her and will march happily with the procession. But a girl who happened to like having her hair down to her heels or loading herself with barbaric gauds and trailing garments or (most awful of all) leaving her nose in its natural state – she will still be well advised to do these things on her own premises.

2 Comments

I just recently discovered this article (in Medium). This is the second quote from Chesterton that I’ve come across, being used in Julia Galef’s book The Scout Mindset. Chesterton’s argument, like Pascal’s Wager does, on the surface, seem to present a good case, but delving deeper reveals a lot of problems. His screed is simply an ad hominem wrapped in a false dichotomy, wrapped in a strawman argument. If Chesterton’s fence represents the existence of a law, say requiring the ability to read before voting, then defending the fence is problematic. For Chesterton, his motivated reasoning only allows for the intelligent reformer (him) and the “more modern,” and thus unintelligent, reformer (young people). What Chesterton doesn’t allow for is the reasonable reformer (questioning, weighing the issues, and determining the best course of action). He clearly demonstrates what Douglas Adams says, that reasonable people hold this view as evidenced by this view is held by reasonable people.

It’s purely a rant against changes in society, and Chesterton is indulging in the time-honored tradition stretching back to ancient Greece of griping about the younger generation (which was raised by the gripers).

(The problem with Pascal’s Wager is if you “believe” in God only because it’s the safest bet, then wouldn’t a God that can see into your heart of hearts know this and understand that you don’t truly believe?)

Thanks for the article. Very enjoyable.

Thanks Sean, I appreciate the feedback. Chesterton’s straw man argument has many faces!

(Pascal’s Wager needs to be understood in the context of Pascal’s specific Jansenist beliefs, which centre on free choice.)