The Rabbit Warren

One of the reasons why Slate Star Codex (SSC) was so successful is that it’s often a rabbit hole of links that readers can dive into – or more specifically a rabbit warren which connects across multiple posts on multiple subjects, all promising to build into a coherent narrative based on knowledge which is hidden to all but the initiated, for whom it is in plain sight. Let’s dive into one of those rabbit holes.

The NYT wrote a fairly dire article on SSC which was received by the rationalist community as a hit job. Partly as a response, Tom Chivers of Unherd wrote a lament that nobody on the web tries to persuade anybody any more; to his mind, Scott Alexander of Slate Star Codex (formerly) and Astral Codex Ten (currently) is one of the few who genuinely makes an attempt to persuade people of his views, or at least to reconsider their own views.

I agree it’s a little violin music that the NYT article fails to explain the positive side to Scott Alexander’s writing. In one memorable mis-step (and I tend to believe it was bad writing rather than bad faith), the writer Cade Metz writes that

In one post, [Alexander] aligned himself with Charles Murray, who proposed a link between race and I.Q. in “The Bell Curve.” In another, he pointed out that Mr. Murray believes Black people “are genetically less intelligent than white people.”

Chivers described this moment as “perilously close to outright misrepresentation… in essence, guilt by association” and pointed out that “the line in which he “aligns himself” with Murray is on whether there is a genetic component to poverty (which surely there must be), not race: race is not mentioned in the post at all.”

This is not what Chivers wanted to write about, but this point captures the problem with Scott Alexander’s writing, and points towards a problem with rationalists. It turned into a quite vigorous thread on Twitter which sadly never stood a chance of going viral because it was an intelligible and respectful exchange of views – exactly what Tom was hoping for in his article, in fact – but I came away from it feeling dissatisfied.

And that’s why I’m writing this.

Guilt by Association

If we revisit the SSC article in which Charles Murray makes an unscheduled appearance, we find SSC doing what SSC does best, which is writing a wall of text with a huge signal to noise ratio while making up an oversimplified analytical framework to explain himself. (I had to get that out of the way, because these are two of the most frustrating things about Scott Alexander’s writing.)

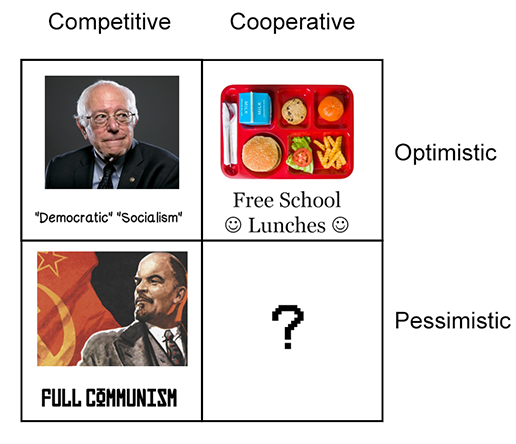

The framework isn’t that complicated; it’s an internet-ready “political compass” that tries to capture different views about poverty. Alexander admits that “[t]hese are all going to be straw men, but hopefully useful straw men”, but unfortunately hanging a lampshade on Wurzel Gummidge is not a defense. Nobody forced Alexander to write this piece, and nobody forced him to massively oversimplify these positions (his words, not mine), and he’s never averse to increasing his word count – so really this is just rhetoric.

Anyway: Alexander places himself in the south-east quadrant, where “Cooperative” and “Pessimistic” intersect, “a very gloomy quadrant, and I don’t blame people for not wanting to be in it. But it’s where I spend most of my time.” People in this quadrant “think that we’re all in this together, but that helping the poor is really hard”, and apparently the only other public figure in this quadrant he can think of is… Charles Murray.

This is an astonishing thing to write. I can think of several public figures who fit comfortably in that quadrant, including Esther Duflo, Abhijit Banerjee and Michael Kremer. They might not be as notorious as Charles Murray, but I think winning the Nobel Prize in Economics for your work on alleviating global poverty probably counts for something. In fact the dominant position amongst those who work on global poverty is exactly that south-east quadrant; it’s an extremely crowded place, and I’m not even sure that Charles Murray can be seen.

The north-east quadrant is described as “people who think we’re all in this together and there are lots of opportunities to help”. It does not require eagle eyes to notice that “lots of opportunities to help” and “helping is really hard” are not contrary views, which is a useful example of how Alexander is either engaging in surprisingly sloppy thinking or deliberately stacking the deck. The whole framework reads like a bullshit culture war meme to me, but I accept it may not look like that to Alexander.

So maybe I was wrong two paragraphs ago. Maybe a more accurate description of the south-east would be “people who feel like it’s all too much”, while the north-east is better described as “people who actually work on these issues”. If we’re really going for it, the description “people who actually work on these issues” probably refers to the north-east, north-west and south-west quadrants, because it is noticeable that communists, anarchists and theocrats (who Alexander shares the “Pessimist” label with) frequently do attempt to ameliorate poverty through e.g. mutual aid. From that perspective it is very difficult to see who’s left in the south-east quadrant.

The charitable conclusion to draw from this is that Alexander doesn’t actually know very much about poverty. What he does know something about is the nature vs nurture debate and its connection to income, which he conflates with poverty, and he aligns himself with Charles Murray only in that he agrees that differences in income “are up to fifty-eight percent heritable” and that “[n]either he nor I would dare reduce all class differences to heredity”.

I’m not interested in Charles Murray because he makes me very sleepy, but I am interested in the idea that income differences “are up to fifty-eight percent heritable”. Unfortunately the link on SSC is dead, but a quick search reveals that it probably linked to a version of a paper titled “The Promises and Pitfalls of Genoeconomics” (same lead author, adjacent publication year, and that 58% figure tucked away in a table), which predicted that “genoeconomics will ultimately make significant contributions to economics”.

That paper was from 2012 – what’s happened since then?

Pitfalls and Promises

As if to prove my Rabbit Warren thesis, the NYT published an article on genoeconomics in 2018 which of course I had to read. The lead author of the 2012 paper, Daniel Benjamin, features heavily, and there is A LOT going on in the article. One of the things that’s going on in the article is this:

If what Benjamin’s study claims to measure is controversial, consider what it doesn’t measure. The study only draws on the DNA of white people — Europeans, Icelanders, Caucasians in North America, Australia and the United Kingdom. And that’s in part because only those groups, along with Chinese nationals, have given over their D.N.A. in large enough numbers to achieve the statistical power that geno-economics researchers need… even if the same numbers of people from all races provided their data, one group would still have to be excluded from the study: people with recent genetic roots in Africa, which is to say both Africans, African-Americans and many Latinos… the genes of people within the much larger, much more ancient gene pool of Africa (including those brought to the United States and elsewhere by slavery) are so much more diverse that researchers would need a far larger sample — at least two or three times as large, Benjamin says — to even have a hope of finding measurable patterns. Benjamin and his collaborators in fact tried applying the polygenic score derived from European DNA to African-Americans and found the method didn’t work well enough to be useful.

This seems like a sizeable gap in the data if you want to draw conclusions about poverty in the US, let alone at the global level. I’ll admit that if they ever manage to get a sufficiently large sample, the results stand a good chance of being similar, but this is still worth bearing in mind, because the problem is not infrequent across scientific research. The NYT article gives a lot of space to the ethics of this research, and if you don’t have the stats chops to read the 2012 paper, the NYT article will get you most of the way there on the overall aim of genoeconomics. But if you do read the 2012 paper, it describes the economic outcomes that they focused on:

we constructed the following eight “economic outcomes” that serve as dependent variables in the analysis: (a) time preference index (an index of present-oriented behaviors, combining measures of alcohol use, cigarette use, and body mass index at age 25), (b) happiness, (c) self-reported health, (d) housing wealth, (e) human capital index (an index of human capital, combining years of education with number of foreign languages learned), (f) income (predicted by occupation held at midlife), (g) labor supply, and (e) social capital index (an index of social capital, combining the amount of regular contact with relatives and friends, attendance at religious services, and participation in social activities).

What Scott Alexander believes – and what Tom Chivers picked up in our tangential twitter exchange – is that these sorts of economic outcomes are strongly influenced by heritable traits (conscientiousness, for example), and that by extension poverty is influenced by genetics. Alexander – like Charles Murray – believes that this should inform our attempts to reduce poverty, and that if we ignore them then we are doomed to failure.

There’s only two problems with this reasoning. The first is that it’s largely irrelevant, and the second is also that it’s largely irrelevant.

The First Irrelevance

When we started the discussion, Chivers clarified his position:

Someone pointed out to me that if I’d said “earnings” rather than “poverty” it might have been less controversial. There is a non-zero correlation between certain… traits (including intelligence and conscientiousness) and earning power. There are many other factors involved, but I *hope* we would agree that, if all else were entirely equal, being clever and being hardworking is an advantage in the workplace and will, on average though not in every case, bring some increased earning power. I would also argue that earning power is correlated with wealth. Again, it’s not the only factor, there are many other things going on including family money, but it is a factor. And I think it is well-established that all personality traits, including intelligence and conscientiousness, are partly hereditary; we can quibble over the exact degree, but it’s non-trivial. So if we accept that personality is partly gene-influenced, that earnings are partly personality-influenced, and that wealth is partly earnings-influenced, we logically have to say that wealth (and therefore poverty) is partly genetically influenced. Of course this says nothing about the scale of that influence, but I do think it is almost unavoidable that there is *a non-zero role* for genes in wealth.

I agree. There is a non-zero role for genes in wealth. However there’s a non-zero role for genes in pretty much everything that humans do, simply by virtue of the fact that humans have genes. That means that claiming a non-zero role for genes in X doesn’t have a lot of explanatory power, which is of course why we still have the nature vs nurture debate. It’s rarely about “whether” any more, and all about “how much”.

The “how much” question is difficult to answer because there’s so much noise along the causal chain – hence why Chivers qualifies his statement with “if all else were entirely equal”, which is a basic requirement for establishing a causal chain. But the longer the chain, the greater the noise, and in his statement above he’s already added two additional links to the original claim that there’s a genetic component to poverty.

First, we’ve moved from “a genetic component” to “certain traits which have a genetic component”; second, we’ve moved from “poverty” to “earnings”. While on the surface these two statements might appear to be equivalent, they are not. The second claim is much weaker than the first, because these are (1) *certain* traits which may have different valences depending on context, (2) in which the extent of the genetic component is unclear, (3) bearing on earnings, which is not the same thing as poverty.

Chivers writes “if we accept that personality is partly gene-influenced, that earnings are partly personality-influenced, and that wealth is partly earnings-influenced, we logically have to say that wealth (and therefore poverty) is partly genetically influenced.” Sure, but remember that Alexander’s claim is that “a lot of variation in class and income is due to genetics and really deep cultural factors”, and here we’re looking at a claim about genetics that has been watered down so much that it’s positively homeopathic.

If you disagree, I understand; but I hope you also understand why I wouldn’t take that claim very seriously without some serious evidence. I don’t think these claims are made out of ignorance or with ill intent; I just think that some people like simple answers to complex questions, particularly people who might be suffering from engineer’s disease. It may or may not be the case that being conscientious correlates with higher income *if all else were entirely equal*, but the whole point about poverty is that all else is very much not equal.

Which brings us to The Second Irrelevance.

The Second Irrelevance

If you remember, the research paper that Alexander linked to described a set of economic outcomes. What I found interesting about them is how disconnected they are from poverty as I understand it, which is based on my experience of working with and for organisations concerned with reducing poverty, and from following the literature on poverty issues as best I can. I subscribe to Sen’s capabilities approach to poverty, which I think captures it best.

So while these economic outcomes are not unrelated to poverty, they represent a peculiarly individualistic view of what constitutes poverty that could only have been developed in the west. When I asked him what he understood by poverty, Chivers replied that he would be happy with a couple of definitions: the Joseph Rowntree Foundation (for the UK) or the World Bank (for worldwide). Both of these present measurements of poverty that fall into what is sometimes referred to as the “dollar-a-day” view which is prevalent in online discourse.

The excellent book Portfolios of the Poor (South East Quadrant) has something to say about this type of measurement. It “powerfully focuses attention on the fact that so much of the planet lives on so little. But it highlights only one slice of what it is to be poor. It captures the fact that incomes are small, but sidelines the equally important reality that incomes are often highly irregular and unpredictable.” Needless to say the reasons why incomes are irregular and unpredictable – and the myriad other external factors that keep people in poverty – do not have a genetic component.

The equally excellent book Poor Economics (South East Quadrant) points out that “What is striking is that even people who are that poor are just like the rest of us in almost every way. We have the same desires and weaknesses; the poor are no less rational than anyone else—quite the contrary. Precisely because they have so little, we often find them putting much careful thought into their choices: They have to be sophisticated economists just to survive…. And this has a lot to do with aspects of our own lives that we take for granted and hardly think about.”

This raises a huge question mark about whether the research findings that Alexander refers to are cause for the pessimism he claims when thinking about poverty. Apart from the social capital index, all of the metrics are things that pertain to the individual, not their family or community, which means that it is blind to factors that operate on that wider canvas. Here’s an example of how people who work on poverty view it, and here’s the 11 causes of poverty they list:

- Inequality and marginalization

- Conflict

- Hunger, Malnutrition and Stunting

- Poor Healthcare Systems – especially for Mothers and Children

- Little or No Access to Clean Water, Sanitation and Hygiene

- Climate Change

- Lack of Education

- Poor Public Works and Infrastructure

- Lack of Government Support

- Lack of Jobs or Livelihood

- Lack of Reserves

And here’s an example of how people who are actually poor view poverty, and the causes they list:

- Being born into a poor household

- Debt

- Ill health and accidents

- Large families

- Disasters

- Migration from rural poverty

- Evictions

- Laziness

- Structural injustice, including lack of ID and credit access

It seems to me that there is no genetic component whatsoever to nearly any of these factors; most of them are either fully external to the community, or structural in nature. The good news is that this means that we don’t have to be pessimistic; reducing poverty is not simple, but there are clear policies which can help to address the causes of poverty. If you’re wondering why people avoid talking about the genetic component of poverty, it’s not because of a moral panic around eugenics; it’s because it’s just not that relevant to policy.

Postscript to Poverty

I’m rationalist-adjacent. I read Slate Star Codex (now Astral Codex Ten) and I subscribe to the Rational Newsletter. I’m interested in many of the same topics that rationalists are, but I am not a rationalist.

Rationalists claim that “Rationality is not a rebuttal to The Narrative but a way to make sense of the world without relying on one”. This is a self-serving delusion. The discussion about poverty shows how the narrative is smuggled in under cover of data.

I’m also not convinced that Alexander is all about the art of persuasion. That might be what Alexander thinks he’s about, but the fact that he massively oversimplifies (again, his words, not mine) on the regular suggests otherwise. He’s preaching largely to the choir.

Where does that leave us? I follow rationalist discussions mainly because I want to test my assumptions; but also because I find it fascinating that people who appear so smart can misapprehend the world in such fundamental ways.

Rationality is like a microscope; train it on one particular spot, and you can learn a lot about that one spot; but you run the risk of missing anything that’s not on that spot. And then you might end up in what you think is the South East Quadrant – but is in fact somewhere else.