In the last ten years there has been a small explosion of forecasts seeking to identify the major trends that will affect relief and development organisations, and to describe how those organisations might prepare to address those trends. Most of these reports are very good, but all of them have a certain scent of panic about them: the sector is alarmed by its own prospects, unconvinced by its own capacity, pressured by its own stakeholders.

This sense of a sinking ship is widely shared by professional aid workers, if not widely articulated: while there is disagreement about how deep are the cracks in the foundation of the humanitarian system, one thing is universally agreed; there is tremendous stress on that system, and the current way of working is not sustainable.

The most obvious symptom of this is financial: the financial needs of the sector are growing, but are not being met. However it’s worth getting some perspective: the $20 billion spent by the humanitarian sector in 2014 might sound like a lot until you find out that the mobile phone app WhatsApp was acquired by Facebook for $19 billion that same year. Despite this relatively small financial presence, humanitarianism is an important part of the international community’s image of itself; it is highly visible, and therefore more important than its budget would suggest.

It was partly in response to these stresses — but more in response to the funding shortfall — that the UN Secretary-General convened the World Humanitarian Summit in Istanbul in May 2016. I’ll let an article by OCHA explain:

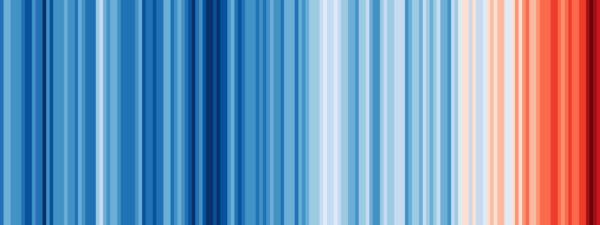

“Humanitarian action has changed tremendously in the past two decades. The numbers of those in need are growing. New challenges, including climate change, resource shortages, and urbanization are placing additional demands on already-stretched resources. New humanitarian actors as well as new technologies are changing how we respond to crises. Now more than ever, we need a new humanitarian agenda for a new era in humanitarian action, one that embraces a wide range of actors, forges new partnerships and spurs more innovative and effective ways of working. How do we get from here to there?”

Now that’s a question worth asking. In this article, I want to sketch out the beginnings of an approach that might get us from here to there, if we’re courageous enough to take it. I know this article is long — most humanitarian staff barely have time to skim the headlines on the Guardian Development Professionals network, let alone battle through 5000 words — but trust me: it will be worth your time.

- Who’s afraid of the big bad future? or, how the humanitarian community talks about the future.

- Why is my crystal ball so cloudy? or, what stops us from talking about possible futures.

- How to think about the Futures or, how things tend to be too near, too far, too low or too high.

- There are no conclusions or, why don’t you tell us how to fix the humanitarian sector?

Who’s afraid of the big bad future?

I want to talk about how the humanitarian community talks about the future: or rather, how it fails to talk about the future in any meaningful sense. Let’s start with that OCHA quote: the “new challenges” it outlines are not new. They’ve all been anticipated for at least 20 years; it’s just that the humanitarian sector collectively failed to register them.

It’s true that “new humanitarian actors as well as new technologies are changing how we respond to crises”, although it’s equally true that the deeper problem is that we’re not changing fast enough to survive. As for the “new humanitarian agenda for a new era in humanitarian action” — well, the outcome of the WHS was not exactly revolutionary. What we got was a re-iteration of some existing commitments, some interesting side discussions about elements of a new humanitarianism, and a missed opportunity for a truly new humanitarian agenda.

(The final outcome of the WHS seems to be generally regarded in the sector as a damp squib, partly because most of the commitments had been on the table for a long time already; some dated back to when I started working in the humanitarian sector in the mid-1990s. The real question is: why is the humanitarian community unable to implement those commitments successfully? That is not the question I seek to answer in this paper, however.)

As I said, the various reports that have been issued over the last decade have been very good, but they have failed to spark the discussion that we need to have. I believe that may be partly because they are simply not pressing far enough ahead; they are failing to represent the astonishing changes that we are likely to live through, and thus failing to force a response from the sector. Future shock can be a useful tool if it’s wielded well.

One of the tools for generating discussion is to use fictional scenarios that speculate about what the world might look like. In particular I’m interested in how science fiction might be used to help us to overcome the psychological and institutional inertia that prevents us from really addressing the future. At a 2015 Futures Roundtable in Geneva (organised in conjunction with the Planning from the Future team at Kings College London) I developed a scenario for the Central African Republic, one of the more intractable emergencies of our time.

Briefing note for new staff: Central African Republic 2030

- What used to be the Central African Republic has quietly disintegrated, as already-porous borders simply became irrelevant to the daily life of communities. The Central African region is now a satellite of the regional economic powerhouses of Central Africa (Douala and Kinshasa) and East Africa (Nairobi and Dar es Salaam).

- The communal conflict of the 2010s have largely subsided, and the twin social networks of trade and religion have merged into trade guilds, widely distributed across the region. Each guild maintains its own mobile-based cryptocurrency, the successors to the e-banking boom of the early 2000s and the bitcoin explosion of the 2010s, and their trade networks rely on a variety of airborne and waterborne drones.

- Trade guilds are linked by mobile telephone infrastructure, and connected to the internet via static balloons and mobile zeppelins funded by the global internet companies. However maintenance of these flying hubs is erratic, and Nairobi-based NGOs provide local mesh networks to ensure that connectivity is maintained when a balloon goes down.

- Just as mobile telephony leapfrogged fixed-line, 3D printing leapfrogged factory production. 3D designs are free, but trade guilds maintain some control through lease agreements for relatively expensive 3D printers and access to the distribution networks for raw materials. These printers, run by local businesses, provide most day-to-day items at low cost.

- Cheap Chinese electronics are still the norm across the region, although African-produced electronics have recently started to appear. On a personal level, this includes low-cost wearable computers customised for communal identification; at a communal level, the falling cost of solar panels has revolutionised domestic life, although distribution remains poor, and electronic waste disposal has now become a critical problem.

- Agricultural work remains central to most peoples’ lives, although it has been transformed by the second industrial revolution. Local farmers experiment with GM crops that have been illegally hacked by the trade guilds; these provide more productive yields but increase the risk of spontaneous genome blight that erupts like wildfire.

- Internet-based private school education (particularly from the regional education hub of Kampala) has lifted many communities into the mainstream economy, although it has also increased tension at the community level, as young people now have higher expectations of future jobs which do not yet exist.

The scenario was intended as a provocation, a test of our imagination: can we really imagine a world that looks like this one?

All the technologies in this scenario currently exist, and the scenario merely extrapolates how the political and economic situation might play out. It is worth emphasising that this not the future, this is one of a range of possible futures: but is it a future that the humanitarian community is anywhere near ready for? What would it even mean for the humanitarian community to be ready for it?

When faced with this kind of scenario, the temptation for many humanitarian professionals is to throw their hands up and suggest that this kind of thinking takes us so far away from the familiar that it becomes impossible to grapple with. Yet grapple with it we must: the future does not allow us to walk away.

The scenario only sounds extreme because most people work out the future by assuming that our current baseline situation will continue, just with more of everything. This growth-based mindset is the result of the specific economic situation that we find ourselves in, reinforced by the historical narratives we are taught, but it consistently fails to predict the future successfully.

“The same, except more” fails to take account of the interlocking nature of current trends, and the consequent way in which network effects operate in our highly-networked world. This type of holistic thinking about the future is largely absent from humanitarian sector — we struggle to prepare even for seasonal emergencies that we know are coming within the year, such as recurrent drought in the Horn of Africa. Yet it is exactly what we need in the humanitarian sector if we want to prepare not just for the next emergency — but for the next type of emergency in the next type of environment.

Why is my crystal ball so cloudy?

In the immortal words of Yogi Berra, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future”. Bearing in mind that the farther ahead you look, the less likely it is that your predictions will be accurate, it’s still possible to extrapolate trends. However these trends emerge not just from the humanitarian sector, but across a range of different domains where our humanitarian expertise may be of limited use. And how wide those domains stretch! Disasters are the outcome of factors across a range of such domains: technological, economic, social, political, environmental, and so on.

While most people think of disasters as being external shocks, many of those factors are internal; which is to say that they are built in to the way in which we collectively organise civilisation. An example of this would be the way in which urbanisation trends increase vulnerability by exposing poor communities to greater environmental risks. These internal trends combine with those external shocks to create disasters: we can think of disasters as shocks from outside the immediate range of institutional capability. Thus the impact of an earthquake is greatly different depending on which city it affects: the type of infrastructure, the nature of governance, the level of poverty.

Some trends are easy to identify: for example, the risk of displacement by disasters has doubled over the forty years since the 1970s. Increased disaster risk has been compounded by the emergence of new types of disaster: the nuclear catastrophe of Fukushima; the urban collapse of Port-au-Prince; and the possibility of even more alarming disasters, such as bio-engineered disease. Some of these trend factors we do already think about in future terms: examples might include the ageing global population, escalating climate change, and rapid urbanisation, all of which can be found in the future-scanning reports that have been described earlier. However there are four problems with how the humanitarian community is attempting to address these issues.

First, our discussions are far behind the curve on nearly all of these issues. These issues were clear 20 years ago, but most humanitarian organisations have still not incorporated them into policy and practice successfully. Take the ageing global population as an example: in 2000, for the first time, there were more people over the age of 60 in the world than children under five. One of my first jobs in the 1990s was with the NGO HelpAge International, who were already campaigning around the demographic transition that would lead to an ageing population. It took HelpAge and others 20 years of campaigning before humanitarian community adopted something resembling a collective position — and in practice, older people are still seldom taken into account in programming.

Second, our discussions typically only address the first-order effects of those trends on our operations, not the second-order impacts on our business model. The ageing population, for example, means that within 30 years, 80% of older people globally will live in developing countries, and 80% of those will have no regular income, and it’s therefore critical that we address the needs of older people in emergencies more effectively. What we’re missing is that an ageing population in critical donor countries also means a smaller tax base and less disposable income — the source of most of our funding — and potentially more conservative social and economic policies that might reduce the level of political support for our work.

Third, our discussions fail to explore the inter-relations between different trends. Ageing populations are closely linked to other issues such as immigration and automation — the first being required to replace a shrinking labour force as the population ages, the second being required to reduce the number of jobs for which labour is required, both implying a transition to a completely new economic model. Migration also has implications for the political priorities of donor countries, which will experience shifts in their priorities due to cultural pressures; and automation has implications for humanitarian work more generally, as key humanitarian activities such as shelter and health become increasingly automated.

Fourth, because we are reliant on politicians and the public for our support, and because our main channel of communication is the mass media, our discussions are at the mercy of simplified framings of complex issues. In a recent discussion I was asked how concerns over militant Islam figured in our forecasts for the future. My response is that the situation is produced by and feeds into exactly the same trends as any other — demographic transition, resource constraints, governance struggles, mass migration. That doesn’t mean that militant Islam is unimportant, but the popular focus on particular militant groups risks missing those broader narratives which are, in the end, more critical to our future plans. The popular alarm generated by terrorism might actually be preventing us from taking a long-range view that might ensure an effective response in the future.

How to think about the Futures

Humans are, as a rule, terrible at predicting the future; and humanitarians are only human. We face the same cognitive challenges as anybody else when it comes to understanding what the future holds. The trends that will shape the future can be too near or too far for us to focus on; they can be beneath the surface of our daily experience, or flying far overhead, making it difficult to see them in the first place.

First, too near. The fact that smartphones are actually computers that happen to make telephone calls, with massive implications for all aspects of society, has yet to really be recognised by the humanitarian community. Like everybody in the west, we underestimate the astonishingly rapid spread of smartphones: in 2014 there were 2.6 billion, which is predicted to rise to 5.9 billion by 2020; in 2014 mobile internet access as available to 33% of the global population, predicted to rise to 49% by 2020. This is the fastest technology dissemination in the history of the world. Another trend in this category is renewable energy, whose costs have plummeted in the past 15 years without most people noticing, but whose impact has yet to be fully realised. In operational terms, cheap solar energy is likely to revolutionise many of the places that we work; but in broader terms, the transition from fossil fuels has already become turbulent. If post-industrial societies fail to make the transition, what will those societies look like when the cheap energy they rely on is gone?

Second, too far. Last year saw the rise of CRISPR, “the Microsoft Word of gene editing” — actually “a naturally-occurring, ancient defense mechanism found in a wide range of bacteria”, but one that has a wide range of predicted uses. These include removing malaria from mosquitos, eliminating many forms of cancer, treating HIV and other diseases, and accelerating agricultural development. Changes in the means of production — such as automation, combined with new manufacturing models such as 3D printing — are also worth tracking. The World Economic Forum predicts that by 2020, the developed economies will have lost 5 million jobs. It’s not just developed economies that will feel this impact: “69% of jobs in India and 77% in China are at “high risk” of automation”, according to a report by the Oxford Martin School. It’s impossible to predict what impact these developments will have, but one thing is for sure — the world after automation will not work like the world before.

Beneath the surface are the factors that we don’t really think about at all — the complex social and economic developments that are difficult to see clearly even while we’re living them. One of the critical axes in human civilisation is the balance between the individual and the collective: the turbulent political history of the twentieth century was at least partly based around attempts to shift this balance. The atomisation of advanced capitalist societies can be similarly seen in more recently developing economies such as India or China, with similarly disruptive and disturbing impact on the political and social order.

This might sound a little abstract to a humanitarian professional; but the entire humanitarian endeavour is based on the dignity of the individual, to whom human rights are assigned. The business model of the sector is based on appeals to the individual — think about our fundraising material, which tells stories about affected individuals that directly target individual donors. Yet what if this level of individual freedom is a temporary phase in human history, and the pendulum swings back towards communal thinking? The debate about the atomisation versus communalisation is unlikely to be settled any time soon, but it is also unlikely to be settled smoothly, and the effect on our institutions is likely to be large.

Related to this tension between the individual and communal, there are increasing challenges to state sovereignty, and even to the idea of the nation-state itself. Some argue that we are moving slowly and painfully towards a post-Westphalian model, i.e. a world in which nation-states are not the primary geopolitical actor. We see this through secessions (Somaliland), federation (the EU), “empires” (the Islamic State), and functional city-states such as Dubai. The United Nations — the entire international system — is based on a very specific conception of the state, and these new actors disrupt or deny that conception. At the other end, attempts to build over the nation state have an uncertain future: in 2016 the EU looks increasingly unstable, and it would have a huge impact on our funding model if the EU fell apart as its members walked away.

All this leaves not just UN agencies — bound by mandate to work with governments — in an uncertain position, but also NGOs. NGOs are Non-Governmental Organisations, and the particular type of government they are defined against is the sovereign government of the nation-state. It’s not just the terminology that will need to change; NGOs will need to develop a new operating model, a range of different tools for dealing with different styles of statecraft. Some of our old tactics remain viable, particularly on the ground, but our headquarter offices are pursuing an outdated style of statecraft that they were never very good at in the first place.

For example, the number of countries where humanitarian organisations are tolerated could well grow shorter in coming years: the combative attitude of the Sudanese government to international organisations might become the norm. One way of working around constraints such as this is acting through networks rather than through individual organisations. The most obvious examples, and the ones which the humanitarian community is now starting to recognise, are the religious networks that operate in most countries where we work. What would it mean for a humanitarian INGO to look more like a church network?

One of the reasons we look on religious networks with jealousy is that they often receive higher levels of trust from communities. A recent survey by the Edelman Trust showed that, while NGOs still rate higher in terms of trust amongst their public than government or media institutions, they have also suffered the biggest decline in trust. This is critical because our mandates are self-ascribed, with no basis in objective reality: our credibility is based entirely on the public’s trust in us. We are losing that trust partly because people have different expectations of organisations now — in a world increasingly shaped by the internet, our communications are failing to engage the public.

Flying far overhead are risks that are simply beyond us. Existential risks to civilization have been receiving increasing attention: risks such as artificial intelligence, space impacts, global pandemics and the like. I don’t have much to say about these: one dispiriting finding from our futures work is that the existing humanitarian system is essentially useless in such scenarios. The organisations we work for are as likely to collapse as any other type of organisation.

And collapse is always a possibility. It is easy to forget that our organisations are the products of historical contingency. They were created in particular places at particular times, often in response to specific events, and they were shaped by wider forces which were often opaque to those of us working in the sector (for example, the Cold War provided incentives for post-colonial support to emerging states by the West). For the sake of argument let us assume that they were fit for purpose at the times they were created; do we really think that the same business model continues to be fit for purpose given how much those times have changed?

Think about how commerce has been transformed by the rise of container shipping: think about how geopolitics has been transformed by the end of the Cold War; think about how society has been transformed by the internet. Nobody predicted the fall of communism, let alone what came after. Nobody predicted the arrival of the internet, let alone what came after. Nobody predicted the war on terror, let alone what came after. Nobody predicted the financial crisis, let alone what came after.

The world in which we were created is gone, and we barely notice because we lived through it. The humanitarian sector has survived so far, but all of these trends have undermined our authority and our capacity. There is no reason to think that our sector will be immune to future changes, and no reason to think that we have a right to survive.

The future is a big place. The trends described above are bigger than the humanitarian sector. The challenges and opportunities that those trends present are difficult to articulate. They will define and redefine our lives in ways that we cannot predict. It is therefore tempting to avoid thinking about these issues, particularly when it feels as if there is no way that we can address them, either individually or collectively.

This reasoning is wrong. Avoiding the future is not an option, and so avoiding thinking about the future is precisely the wrong way to prepare ourselves for that future. While we can’t predict the future, we can prepare for it: not in the sense of having contingency plans ready for every possibility, but in the sense of ensuring that our organisations are agile and flexible enough to creatively respond to those possibilities. At present we are ill-equipped for the day-to-day task of reconciling those big picture trends with the operational realities of our organisations’ work — the nitty gritty of future-proofing our organisations.

There are no conclusions

Following the end of the Cold War and the start of the War on Terror, political and financial support for an independent humanitarian sector is evaporating. With the rise of middle-income countries, particularly in Africa, governments have become more assertive about the role of international organisations, particularly NGOs. The short version: the old space that humanitarianism previously occupied within the top-down hierarchy of the international system is disappearing.

That’s the bad news, but there is good news. More middle-income countries means more resources for disaster response within countries, especially as mobile technology and internet access enable more self-organisation by communities affected by disasters. The internet has also forced the private sector to move towards networked ways of working, while also creating new forms of bottom-up collaboration. The short version: a new space for humanitarianism is emerging in the networked world.

This space requires that roles, responsibilities and resources are more evenly distributed between a larger number of actors than is currently the case. The drive towards localisation was a significant and welcome outcome of the WHS, but even our language lets us down. “Localisation” relies on a distinction between “local” and “global” — but what’s really being discussed is “peripheral” and “central” respectively. The centre no longer holds.

We cannot and should not preserve the aid system as it currently exists, although there are certainly lessons to be learned from past experience and good practice to be disseminated in any new system. I’ll say it again: predicting the future is impossible, but we can prepare for the futures, by deliberately designing a new humanitarian ecosystem that can survive in this new environment. What form that ecosystem takes is not up to me decide — it’s something that we have to approach collectively, otherwise it will fail — butwhile I don’t have any answers, I do have some strategies.

New methods. There are a range of tools that need to be incorporated into our organisations. Some of these relate directly to the future: we need better methods for forecasting, running from short-term probabilistic assessment of likely events and their impacts all the way to long-term horizon-scanning that can track the trends described in this paper. By itself this is not enough: we need better ways of incorporating this and other learning into our existing work flows, in order to steer those work flows in more productive directions. This means that planning must be evidence-based and holistic, responding quickly to changes in the external environment across the full range of organisational roles. It is often said that military forces spend 95% of their time preparing and 5% responding; currently the humanitarian sector runs the reverse of this, and with only 5% of our time spent preparing it is no surprise that we are so often unprepared. The only way to develop new ways of working is by incorporating innovation into structures, rather than isolating it in departments within organisations, and ensuring that we are flexible enough to adopt (and discard) new technologies more rapidly than at present.

New forms. These new approaches do not sit well in our current organisational structures; and if we adopt such approaches, they will change those structures. We need to be ahead of the curve in this regard: rather than responding (often too late) to new developments and new requirements, we need to build organisations that can be one step ahead — or at the very least, avoid building organisations that are one step behind. In practice this means that we restructure our organisations around the principles of the network, and not the hierarchy we have inherited from our industrial history. This will mean relying on smaller, modular organisational units that can be rapidly and specifically configured to respond to emergencies, rather than relying on a one-size-fits-all industrial approach. This restructuring needs to be across entire organisations: not just perational areas such as health and WASH, but also in logistics, human resources, and so on. While elements of the industrial model may be retained, these professional skills are already being reshaped in the wider world of work.

New people: Our current staff will be unable to implement these new approaches or develop these new forms. To some extent this is a generational divide — younger staff are much better equipped to deal with the changed world we live in — but we need to get a balance between new vision and old experience. Many of the key aspects of disaster response will remain the same, and the lessons we have learned in the past can guide us in the future. We must avoid at all costs Year Zero thinking, where every generation discovers aid work anew. We also need different skills — two examples that I have advocated for in the past is that we need more professional statisticians and urban planners working with our organisations, and I have recently added privacy advocates to that list. However the real need is not so much for specialist skills, but for staff who can understand this new way of working through the network; not just to deliver the project, but to reinforce a new culture of humanitarian values.

We are not adopting and combining these three aspects for their own sake, but to create a new culture within the humanitarian sector — a networked approach that is more flexible and resilient than the current hierarchical structures. The present trend in aid is towards effectiveness as the paramount value, but this is not a sufficient value to sustain the humanitarian sector. Part of this networked approach will be a move from a primarily transactional culture (based on contracts) to a predominantly relational culture (based on values) that can successfully characterise core humanitarian principles that are embodied in the Red Cross Code of Conduct.

I’ve put a lot of emphasis on the importance of maintaining and disseminating humanitarian principles as the key aspect that differentiates humanitarian organisations from organisations that might become involved in relief work — the military, the private sector, and so on. One question that is often asked is how principles propagate through a network. Humanitarian organisations tend to think about principles in hierarchical terms — international treaties are negotiated, organisational policies are agreed, implementing contracts are signed — but in fact this is only half the story. Achieving real change has to balance this hierarchical and transactional approach to principles with an increasing focus on a networked and relational approach. Think of how attitudes towards race, gender, slavery, and so on, have changed over the years: in many cases the law follows social cues, rather than the other way around.

Humanitarian principles should work like this as well: we need to foster a movement to normalise those principles in different cultures, not merely through authority (which is the current model, as exemplified by the Red Cross movement) but through mass mobilisation. The advantage of this approach is that it takes advantage of one of the core characteristics of principles: they are ideas, and ideas are almost impossible to kill. There are currently questions about how to relate to non-traditional donors and implementing partners who may not have humanitarian principles embedded in their work — or even be aware of those principles at all. We can’t expect to strongly influence such organisations directly, but leveraging network effects should make it possible to steer their discourse into a more humanitarian direction, if the principles are embedded in that network.

This is always a complicated dance, and it may turn out that some principles are more susceptible to propagation through the network than others. We also face the challenge that networks are very good at amplifying single issues, but very bad at engaging with holistic process; we need to be part of the process of developing new theories of influence that can mitigate this weakness. However the eventual result may be that the principles will be widespread but weak; such weakness may be something that we just have to live with, if we want the principles to survive at all.

These are huge challenges, and they are piled on top of our day-to-day responsibilities of responding to emergencies, but if we do not address them then we risk becoming not just ineffective but potentially irrelevant. If that happens, then the humanitarian project as it has been historically conceived since the foundation of the Red Cross movement may grind to a halt; and the humanitarian principles that it is based on may become largely irrelevant. Emergency assistance will still be provided, of course — that is unlikely to change — but I think most people working in the sector believe there is an important distinction between the assistance we provide and the basis on which we provide it.

This leads me to the only conclusion I have: when I talk about future-proofing the humanitarian project, I am not necessarily talking about the survival of individual organisations. Those of us with greater power within the existing humanitarian system are likely to see that power evaporate if current trends continue, but while our power still exists, we must use it to ensure the system ensures the survival of the principles we believe in. What I am therefore interested in is ensuring that the structures that come after us — no matter what form they take — embody the humanitarian values that I believe give meaning to our work.

Thanks to Randolph Kent of Kings College London, and all those who have worked with him on the Humanitarian Futures Program and Planning from the Future Initiative.